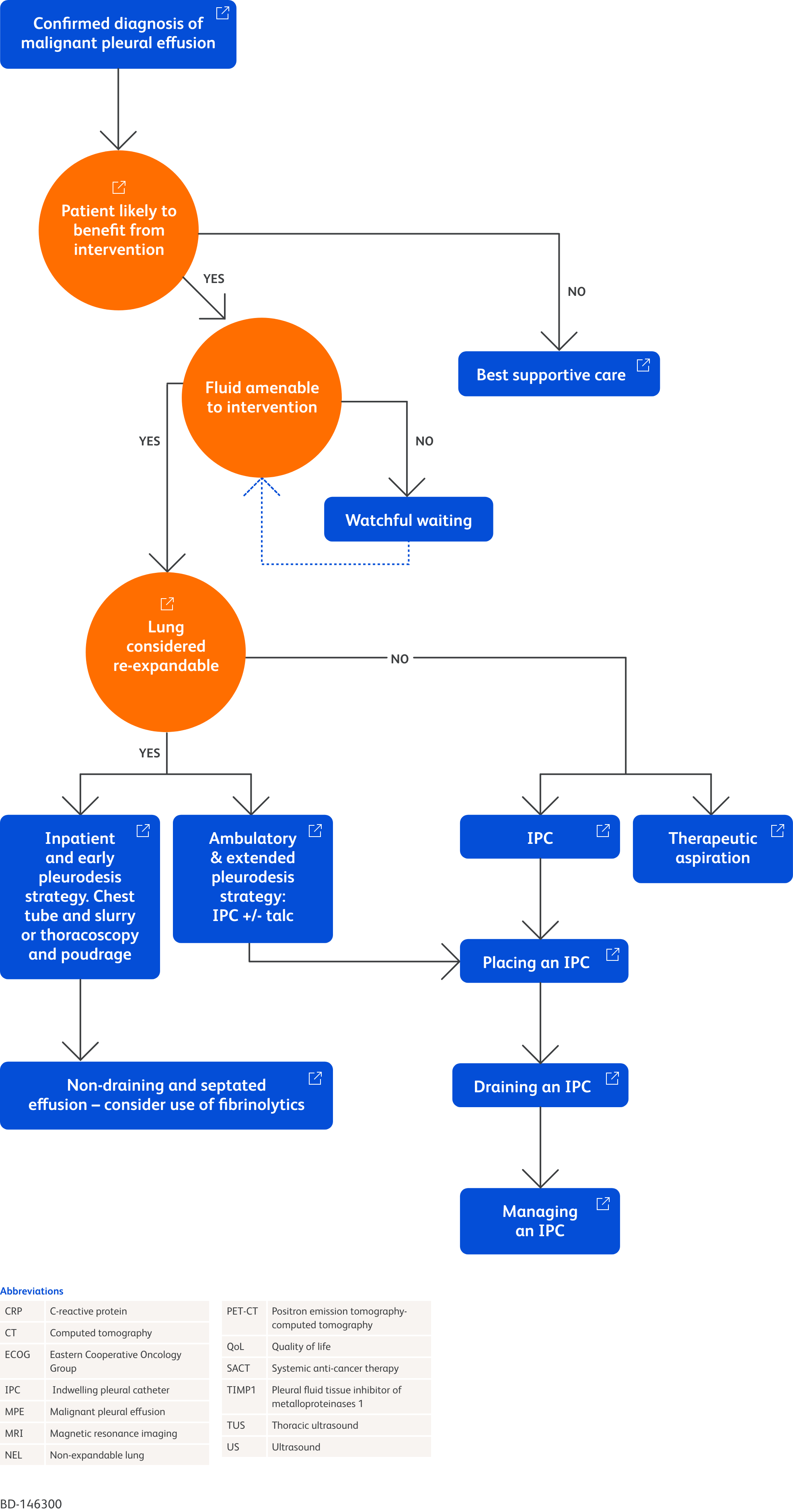

Interactive Care Pathway for Malignant Pleural Effusions

Significant changes in the management of malignant pleural effusion (MPE) have occurred since the British Thoracic Society (BTS) published guidance in 2010.1 Pleural fluid cytology and chest tubes with talc pleurodesis were previously the primary means for diagnosis and treatment, but there are now several evidence-based options for clinicians.1

This interactive care pathway is based on the 2023 update of the British Thoracic Society (BTS) guideline for pleural disease. It is intended as an educational tool to help you navigate the pathway and understand the underlying evidence supporting the various branches. While the BTS guidance ends at the selection of an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC), this pathway goes further to provide educational resources on the proper insertion and management of patients with an IPC.

Click on the nodes of the pathway to learn more and discover additional resources to support you in your understanding of MPE and IPC.

The resources, images, and videos included in this interactive care pathway were selected with the support of a panel of pulmonologists who routinely work with patients with MPE, including Prof Mohammed Munavvar, former President of BTS.

- Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42

Confirmed diagnosis of malignant pleural effusion

A common symptom of MPE is breathlessness, with up to 50% of patients experiencing this.1,2 Other symptoms include fever, fatigue, weakness, chest pain and weight loss.3 Whilst these are common, patients may not experience all of these symptoms.4

Tools such as image-guided pleural biopsy, ultrasound (US) guided pleural aspiration and radiology can assist in the diagnosis of MPE.5

Chest X-ray depicting right pleural effusion6

Image provided by Prof Mohammed Munavvar

Clinical image taken with patient's permission

Pleural biopsy

Image-guided pleural biopsy using a real-time freehand technique can provide an alternative to medical thoracoscopy where there is significant disease in the absence of large amounts of pleural fluid.5,7 Thoracic ultrasound (TUS) can be utilised to visualise the intercostal vessels and prevent them from being punctured.7

Diagnostic pleural aspiration

Diagnostic pleural aspiration should utilise small bore needles (21 G/40 mm), TUS and a sample of around 50 mL should be removed.7

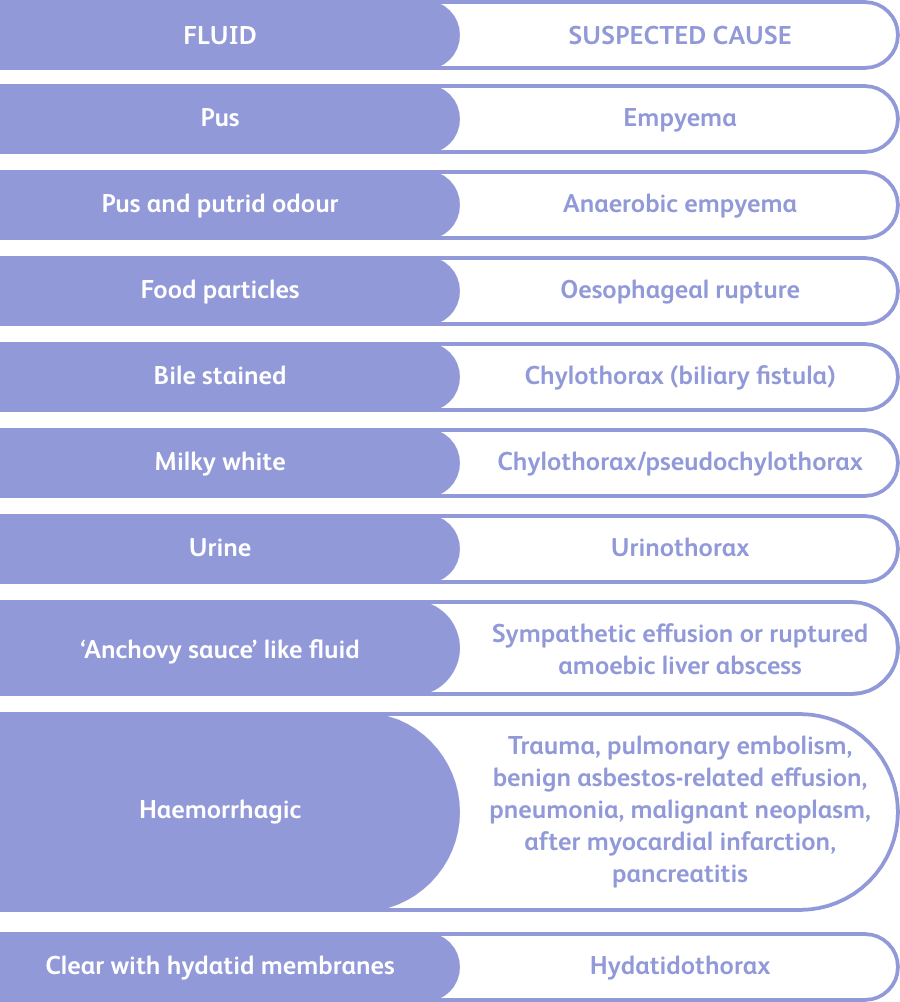

Once a pleural fluid sample has been taken, the appearance of the fluid and any odour should be recorded. The characteristics of the fluid can help to diagnose the patient.8

Diagnostically useful pleural fluid characteristics8

Image adapted from Karkhanis and Joshi, 2012.8

Imaging

TUS, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may support a clinical diagnosis of malignancy.5 CT can be used when a biopsy is not an option, but does not rule out malignancy if negative.5 When CT or clinical features suggest malignancy is present but histological results are negative, PET-CT can be used as an alternative to invasive sampling.5

Good practice points5

- Imaging results should be considered alongside clinical, biochemical and histological results.

- Malignancy may not be seen with imaging. Unless the diagnosis is confirmed with other means (e.g., biopsy), monitoring with follow-up imaging should be taken into account for patients with both pleural thickening and unilateral pleural effusion with no clear explanation.

- The value of MRI in diagnosing pleural malignancy is as yet undetermined and should be reserved for highly selected patients or research.

References

1. Mishra EK, Muruganandan S, Clark A, et al. Breathlessness predicts survival in patients with malignant pleural effusions. Chest 2021;160:351–357.

2. Dixit R, Agarwal K, Gokhroo A, et al. Diagnosis and management options in malignant pleural effusions. Lung India 2017;34:160.

3. Kulandaisamy PC, Kulandaisamy S, Kramer D, et al. Malignant Pleural Effusions – a review of current guidelines and practices. J Clin Med 2021;10:5535.

4. Twose C, Ferris R, Wilson A, et al. Therapeutic thoracentesis symptoms and activity: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023;13(e1):e190–e196.

5. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

6. Prof Mohammed Munavvar. Clinical image taken with patient’s consent.

7. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

8. Karkhanis V, Joshi J. Pleural effusion: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Open Access Emerg Med 2012:31.

BD-109745

Patients likely to benefit from pleurodesis or indwelling pleural catheter (IPC)

Patient-related issues influencing management of malignant pleural effusion (MPE) include:1

- Will drainage of pleural fluid help the patient?

- Is it likely that pleural fluid will accumulate again?

- Is management with pleurodesis or indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) appropriate given the patient’s life expectancy and prognosis?

- What steps can be taken to keep time in hospital to a minimum?

Will aspiration of pleural fluid help the patient?

Since MPE is a marker of advanced disease, symptom management and conserving quality of life (QoL) should be the focus of treatment.2 With regard to respiratory symptoms, less than a quarter of patients are asymptomatic; identifying who will benefit from drainage is largely determined by symptoms, most commonly dyspnoea.1

Is it likely that pleural fluid will accumulate again?

The probability of fluid re-accumulation after initial aspiration is high in MPE, but it is not a certainty.1,2 The use of systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT) to reduce the need for pleural drainage in adult patients with MPE is not supported by evidence.2

Is active treatment appropriate given the patient’s life expectancy and prognosis?

Poor survival rates are associated with MPE, and usually suggests the presence of advanced disease.2 Patient outcomes are influenced by factors such as the results of biochemical and haematological tests, and the characteristics and composition of pleural fluid.2 There are two prognostic scoring systems that have been validated to estimate survival times for MPE, but neither have been assessed in their ability to improve outcomes.2

Predictive scores

LENT

The LENT score combines the level of lactate dehydrogenase present in pleural fluid, the results of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score, the ratio of neutrophils-to-lymphocytes in pleural fluid, and the nature of the tumour.3 LENT scores can predict patients at low, moderate or high risk of mortality, and is superior to using the ECOG performance score alone to predict poor prognosis in patients.4

PROMISE

A prospectively validated prognostic model that combines one biological marker (pleural fluid tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP1)) and seven clinical parameters (ECOG performance score, c-reactive protein (CRP) levels, haemoglobin, white blood cell count, cancer type and history of chemotherapy and radiotherapy) to accurately estimate absolute risk of death at 3 months.5

What steps can be taken to keep time in hospital to a minimum?

Palliative procedures are preferred for MPE where survival is expected to be short, with the aim of maintaining quality of life, and minimising time at the hospital.2,6

References

References

1. Penz E, Watt KN, Hergott CA, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusion: challenges and solutions. Cancer Manag Res 2017;9:229–241.

2. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

3. Jeba J, Cherian RM, Thangakunam B, et al. Prognostic factors of malignant pleural effusion among palliative care outpatients: a retrospective study. Indian J Palliat Care 2018;24(2):184–188.

4. Clive AO, Kahan BC, Hooper CE, et al. Predicting survival in malignant pleural effusion: development and validation of the LENT prognostic score. Thorax 2014;69:1098–1104.

5. Psallidas I, Kanellakis NI, Gerry S, et al. Development and validation of response markers to predict survival and pleurodesis success in patients with malignant pleural effusion (PROMISE): a multicohort analysis. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:930–939.

6. Bibby AC, Dorn P, Psallidas I, et al. ERS/EACTS statement on the management of malignant pleural effusions. Eur Respir J 2018;52:1800349.

BD-160987

British Thoracic Society Guidelines for pleural disease support

Patients with malignant pleural effusion (MPE) should be managed by a multidisciplinary team, including palliative or hospice care teams when needed.1

Education can help to reduce anxiety, and it is helpful for patients and family to appreciate that in the end stages of life, symptom relief to promote quality of life (QoL) can be achieved without invasive procedures.2,3

Supplemental oxygen can be used to increase pulse oximetry readings and reduce respiratory rate and heart rate.2 Medications such as oral morphine can offer pain relief and reduce anxiety.2 Assistance with personal care should be planned so as to reduce the burden on the patient and conserve energy.2 Additionally, high calorie, easy-to-swallow food will help to meet the patients’ respiratory caloric needs.2

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

2. Held-Warmkessel J, Schiech L. Caring for a patient with malignant pleural effusion. Nursing (Brux) 2008;38:43–47.

3. Beyea A, Winzelberg G, Stafford RE. To drain or not to drain: an evidence-based approach to palliative procedures for the management of malignant pleural effusions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:301–306.

BD-109747

Lung considered re-expandable

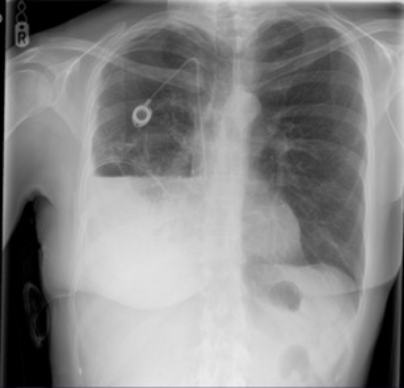

Non-expandable lung (NEL) has been defined on expert group consensus as radiologically significant with more than 25% of the lung not apposed to the chest wall based on chest x-ray appearance.1 NEL includes “visceral pleural thickening that limits re-expansion and endobronchial obstruction that prevents re-expansion”.1 The degree of agreement between clinicians in the interpretation of chest radiographs can vary in the presence of NEL.1

If a patient is undergoing surgical thoracoscopy with the assistance of mechanical ventilation, it may be possible to selectively inflate the collapsed lung prior to completing the procedure, allowing assessment of the chance of re-expansion; however, identification of NEL is not consistent through solely visual means.2

Chest x-ray post-IPC placement with right hydropneumothorax with partial lung entrapment3

Good practice points1

- Patient choice should guide treatment decisions based on a clear discussion of the risks and benefits, including the scarcity of evidence for treatment options for NEL

- Where appropriate, pleural aspiration can be carried out prior to the insertion of an IPC to evaluate symptomatic response

- Alternatives to pleural aspiration (which may need to be repeated) should be discussed with the patient

- In patients with MPE and >25% NEL, the use of an IPC over talc pleurodesis is preferential according to current evidence

- In patients with MPE and <25% NEL, improvements in ‘quality of life, chest pain, breathlessness and pleurodesis rates’ may be seen with talc slurry pleurodesis

- Surgical decortication may improve the rates of pleurodesis in selected patients with MPE and NEL, but the decision to undergo surgery should be discussed with the patient and depends on the individual circumstances of the patient

Resources

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

2. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

3. Prof Mohammed Munavvar. Clinical image taken with patient’s consent.

BD-109748

Therapeutic aspiration

Temporary relief of breathlessness without pleurodesis can be achieved using pleural aspiration, and can prevent patients with poor survival expectancy from being admitted to a hospital.1

Patients will often require multiple procedures as fluid may recur, and discussion with the patient about risks and benefits is merited.1 Pleural aspiration is a relatively low-risk procedure; however, complications can include pneumothorax, haemothorax, re-expansion pulmonary oedema, vasovagal syncope, pain, organ puncture, infection and procedure failure.2

Guidance on therapeutic aspiration procedure2

Preparation

Pleural aspirations should take place under aseptic technique in a designated procedure room rather than “at the bedside”.

Therapeutic fluid removal via gravity or syringe are the recommended means, with use of wall suction or vacuum drainage bottles discouraged. To limit the risk of complications and chance of damaging underlying structures, small-bore needles should be used.

Imaging and site selection

Aspiration must be guided by thoracic ultrasound (TUS). To avoid puncturing intercostal vessels, selecting a site above a rib is preferential.

Volume and speed of drainage

Patient symptoms should guide the maximum volume that should be aspirated in a single attempt, with a recommended limit of 1.5L. Allowing the lungs to expand gradually through slower, controlled drainage may facilitate the earlier identification of complications.

The development of certain symptoms indicate stopping the procedure, namely: chest pain, persistent cough, worsening breathlessness or low oxygen saturation develops. Patients should be monitored following the procedure.

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

2. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

BD-109749

Indwelling pleural catheter

Insertion of an IPC appears to result in a shorter initial stay in hospital and has a lower need for subsequent inpatient days than talc slurry.1,* Treatment choice should be individualised after discussion with the patient.1 Between talc slurry pleurodesis and IPCs, there were no observable differences in improvements in breathlessness,* increase in QoL* and rate of adverse events.1†

For patients with MPE and NEL,* IPCs may improve QoL and breathlessness but the IPC may remain in situ for a prolonged period (>100 days), and thus carries a small risk of infection. MPE patients with less than 25% lung NEL may experience better QoL, reduced symptom burden and better pleurodesis rates using talc slurry pleurodesis compared with IPC; however, no direct evidence supports this BTS Guideline statement.

Good practice points1

- Discussion should take place with the patient about the potential impacts of having a semi-permanent tube drain in situ on mental health and body image

- Community nursing teams should take over care after discharge in order to assess the wound site, support with tasks such as draining the IPC, removing sutures, and advising the patient on how to control their symptoms

- If patients and relatives feel prepared to perform drainage and complete documentation of drainage, they should be trained and supported to do this

- Reassessment by the primary pleural team should be prompted by issues such as an infection that is unable to be controlled by community management, malfunctioning IPC due to fracture, or blockage of the IPC with breathlessness

* Grade analysis not possible, but evidence deemed important by the Guideline Development Group

† Very low evidence

Resources

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

BD-109750

Ambulatory & extended pleurodesis strategy: IPC +/- talc

Combination procedures using a pleurodesis agent administered via an IPC after a period of drainage can be used to improve chest pain, breathlessness, and QoL.1 In an outpatient setting at 35 days after IPC insertion, a 43% rate of pleurodesis was observed with talc instilled via IPC vs a rate of 23% without talc.2 This should be offered to patients with expandable lung when the clinician or patient deems achieving pleurodesis and IPC removal to be important.2

Resources

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

2. Bhatnagar R, Keenan EK, Morley AJ, et al. Outpatient Talc Administration by Indwelling Pleural Catheter for Malignant Effusion. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1313-22.

BD-109751

Inpatient and early pleurodesis strategy: chest tube and slurry OR thoracoscopy and poudrage

Pleurodesis is used to provide long-term control of fluid by creating permanent fusion of pleural layers; however, opinions differ on the optimum talc administration.1 Effective delivery of talc to the pleural space can be achieved by talc slurry administered through a chest drain, or by administration of talc poudrage during thoracoscopy.1

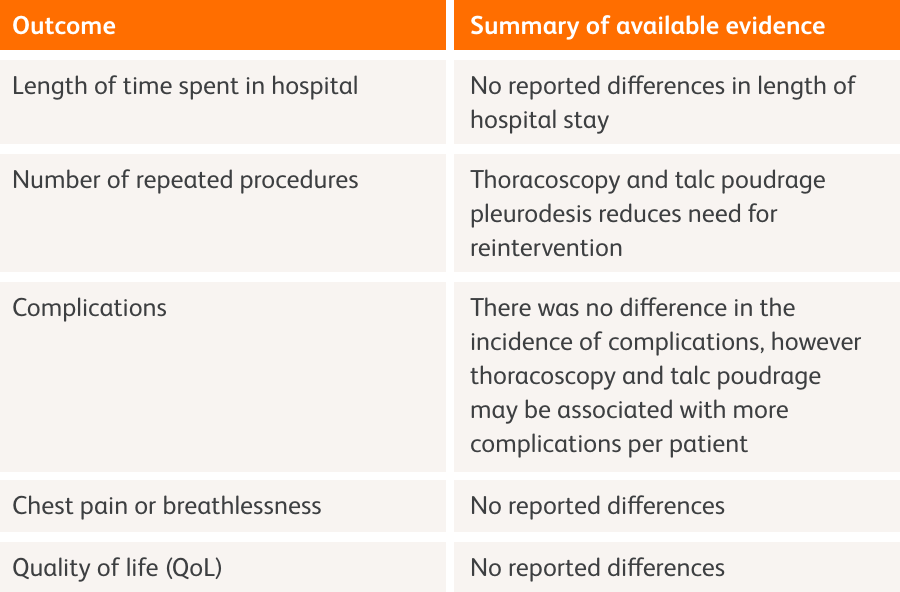

Chest drain and slurry vs. thoracoscopy and poudrage1

Chest tube and slurry

Talc is emulsified in normal saline, and then administered via a chest drain (intercostal tube).1,2 This may reduce the overall number of complications compared to talc poudrage. Management of MPE using talc pleurodesis (or another method) is recommended in preference to repeated aspiration especially in those with a better prognosis, but the relative risks and benefits should be discussed with the patient.1

Talc slurry vs. IPCs

The use of talc slurry pleurodesis or IPCs can appear to improve patients’ dyspnoea and QoL, with no noted differences in QoL or adverse events favouring either treatment. Compared with talc slurry, IPCs appear to be associated with decreased hospital stay (measured as length of initial hospital stay and subsequent inpatient days), and less need for additional pleural intervention.1

Guidance on chest drain insertion

The size of drain inserted impacts recovery and usability. Smaller drains generally cause less discomfort or pain, both during insertion and while in place; however, smaller drains may easily block with talc particles, or kink, making larger drains more suitable for pleurodesis.2

*Grade analysis not possible, but evidence deemed important by the Guideline Development Group.

Resources

Thoracoscopy and poudrage

Talc is administered as an aerosol during thoracoscopy. The ability to visualise the talc directly may result in improved coverage of the pleural space. Despite thoracoscopy being more invasive, talc can be delivered in the same procedure as drainage, leading to a shorter length of hospital stay. Pleurodesis failure rate may be lower with this method but may cause a per patient increase in the amount of complications.1

Good practice points

- In cases of diagnostic thoracoscopy, where appropriate, talc pleurodesis via poudrage should be implemented as part of the procedure1

Resources

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

2. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

BD-109752

Non-draining and septated effusion: consider use of fibrinolytics

In some patients, septations develop within the pleural fluid.1 This separation into pockets occurs as a result of fibrin aggregation and mean that percutaneous drainage cannot effectively aspirate the fluid.1 As a result, patients with septations may have a worse prognosis than other patients.2 For ambulant patients with IPCs, intrapleural fibrinolytics may improve breathlessness, but symptomatic loculation frequently recurs.2*

*Grade analysis not possible, but evidence deemed important by the Guideline Development Group.

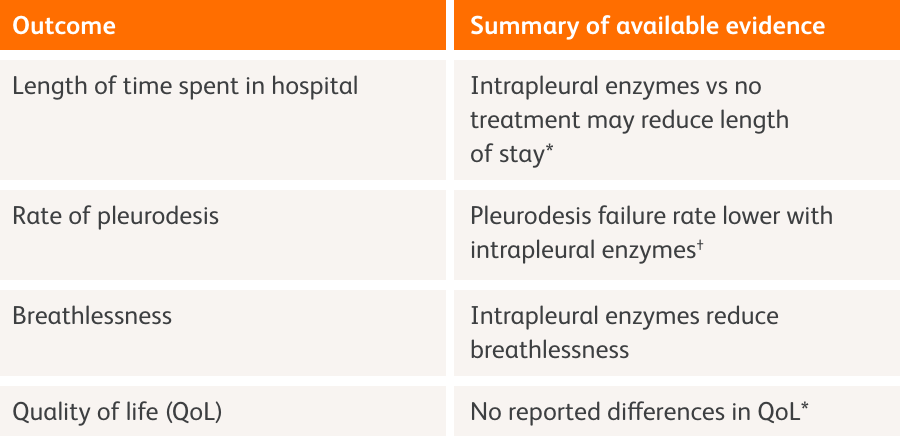

Evidence summary for intrapleural enzymes vs. surgery or no treatment for malignant pleural effusion (MPE) and septated effusion2

*Based on a single study

†Meta-analysis results reported as per 1000 patients

There is insufficient evidence to say if intrapleural enzymes work better than surgery for adults with MPE and septated fluid in the lungs (shown on X-rays).2

Good practice points2

- Breathlessness may be improved in highly selected MPE patients with symptoms using intrapleural fibrinolytics

- If poor drainage of IPCs is not improved by flushing with normal or heparinised saline, intrapleural fibrinolytics may improve drainage

- In a small number of patients with significantly septated MPE who otherwise have a good prognosis and performance status, surgery may help to alleviate symptoms

Resources

References

1. Banka R, Terrington D, Mishra EK. Management of septated malignant pleural effusions. Curr Pulmonol Rep 2018;7(1):1–5.

2. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

BD-109753

Placing an IPC

Sedation during IPC insertion may be required for patient comfort, however, local anaesthetic without sedation may also be used. Thoracic ultrasound (TUS) should be used to mark the insertion points for the IPC. Anatomical variations and patient comfort should be taken into account, as this may alter the insertion sites. Chest X-rays can confirm correct IPC position and look for immediate complications. Patients are usually discharged home on the same day.1

References

1. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Online Appendix 5. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

BD-109754

Draining an IPC

Drainage frequency should be guided by patient choice. Typically, drainage should start at a frequency of 3 times per week unless aiming for pleurodesis in those with expansile lungs where IPC drainage should be as often tolerable (e.g., daily).1,2 In case of pain during the procedure, the rate of drainage should be slowed or stopped.3 Daily drainage is not required to provide symptom control, thus patients should be advised that less intensive regimes are possible, if preferred.1 At-home drainage can be performed by a community nurse, or by the patient or a relative confident in the procedure.2

Resources

Video: “BD PleurX Patient Education – Draining Fluid”

References

1. Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023;78:s1–s42.

2. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

3. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Online Appendix 9. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

BD-109755

Managing an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC)

After sutures are removed, patients can bathe and swim, but care should be taken to keep the IPC site clean and dry (e.g., use of waterproof dressing or prompt replacement of wet dressing). If an IPC infection is suspected, antibiotic therapy should be initiated. Removal of an IPC should be considered when certain criteria have been met:

- <50 mL is drained on three consecutive occasions

- no symptoms of fluid re-accumulation

- no substantial residual pleural effusion on imaging.

References

1. Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023;78:s43–s68.

BD-152010